$elling Your Work

A true living legend outlines some things that will help you move your carvings.

There is always a first for everything. I remember the first time I sold one of my carvings. It was actually a donation I made to Ducks Unlimited, a 2 /3-scale flying pintail that brought $75 at auction. I was on cloud nine thinking one of my carvings could sell for that much. (This was 50 years ago.) Since then, my relationship with Ducks Unlimited has grown several years later a pair of life-size flying pintails brought in $10,000 at the national auction in Boston.

One thing I’ve learned over the years is how to sell my carvings. Sales is an art in itself, and as such it comes with structure and rules. You must learn the rules before you can bend or break them. If you want to be successful at selling your work, you should first familiarize yourself with some of the basics. Once you do, you might find that sales can be just as creative and rewarding as any other art form. In the world of sales, some things may seem evident but people often overlook them. First, separate yourself from your ego. If a potential customer says no, they are saying no to the deal not to you. Figure out a different deal and the difference is not always just price. It can be a matter of timing, or a change in the carving’s mount.

Second, smile! Some exhibitors at carving shows sit scowling behind their displays, almost as though they are daring potential customers to approach. Arrange your display so that you can get to the customer and easily engage in conversation. When you complete a sale, make a point to remember the person and the transaction so you have something to build on in subsequent meetings. It helps to write transactions down with specific information about where you made the sale and under what circumstances.

When interacting with potential customers, talk about anything but the carving. Let your customers relax. They already appreciate the art form, otherwise they would not be at a show. Ask questions—Where are you from? What kind of work do you do? What type of carving do you like to collect? Gradually come back to the carving they are considering. Talk sparingly about technique and more about the “look,” the “brightness,” the “mood,” and the “motion” within the carving. When appropriate, talk about how the mount and the carving complement each other. Point out how the composition creates a sense of motion, and how a sculpture should be viewable from all directions. Refer to the piece as a sculpture, which it is, in the medium of wood.

First-time buyers might need some education, so be patient with them. Tell them to buy what they like, and not necessarily as an investment, even though many carvings will appreciate in value. Remember, when customers buy your work, they will start to think of you as their personal carver.

Do not use all your ammunition—learn to anticipate the “close.” A customer will almost always offer a close, often a very subtle one. You need to learn to recognize these subtleties. If you keep talking past the close, you will probably lose the sale. When the customer says, “I really like the carving but I don’t know where I would put it,” I say, “Oh you will find a place. There is always room for one more.” Then I ask, “How would you like to pay? I take cash, checks, or credit cards.” (If you are not set up for cards, I suggest you do so. More and more people pay only with cards.)

Create a niche market. A carver might become known for his or her buffleheads, redheads, or teal. Maybe you can talk a customer into commissioning all three teal species that visit the United States. Study other successful carvers who do shows regularly. You can learn a great deal from them.

Don’t overlook the “wow” factor. When I spent my summers preparing for the fall shows, I always created a few large, complicated pieces. One year I sold them all by early September. Later that fall I saw a lady looking closely at my display. Finally, she looked at me. “You have no ‘wow,’” she said. “What happened?” I had to explain that I had sold it all. So, it’s good to always have some “wow” on your table. However, make sure you don’t take your “wow” pieces to the same show twice.

Once you have sold a piece to someone new, you’ve done the hardest work. That first sale is always the most difficult. It’s a good idea to put together a customer list for each show (there will be some overlap) and make sure to send each customer a note saying, among other things, that you will be back at the show, that you have a really special carving you think they would like, and that, in any event, you would like to see them. Also, send them a show schedule. This generates interest. Everyone likes to feel special.

-

When you’re selling at a show, it’s a good idea to include something with the “wow” factor to impress potential customers. This life-size flying Canada goose fits the bill.

-

These buffleheads and ruddys formed part of a collection I launched, called the Susquehanna Collection. The collection idea once again led to strong sales.

-

This surf scoter and eared grebe were both part of what I called my Millennium Collection. Launched in 2000, it consisted of 16 pairs of fancy hunting decoys of unusual species. It proved to be very successful for me. The red-breasted merganser is one of my favorite birds to carve. It’s best to carve what you like—customers can tell when you’re bored by a subject.

-

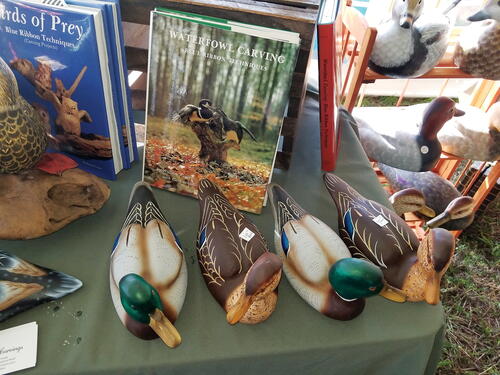

It’s always a good idea to have a lot of variety on your table at a show. I include not only my carvings, but also copies of my books. The life-size pair of black ducks gave me the “wow” factor I always include. The mallards are inexpensive birds I aimed at beginning collectors.

-

If you think there’s a lot of “wow” in one life-size flying goose, see what happens when you carve two

HERE ARE SOME OTHER IMPORTANT DO’S AND DON’TS THAT WILL HELP YOU BOOST SALES.

-

If you carve to sell, make pairs. In this time of impermanent relationships, people like to think that something is permanent. If married customers break up, they can also divide the pairs. (However, if you carve for competition, don’t carve pairs unless the category calls for that. The reason is simple: You cannot win two blue ribbons with the same species at the same show.)

-

Buy and sell a limited amount of related merchandise, preferably smaller items like jewelry, songbirds, books, and so forth.

-

Carve different grades of work. If you do mostly decorative pieces, carve some hunting decoys or contemporary antiques, or vice versa.

-

If you are capable of producing a great deal of work, consider creating a collection. For example, carve miniature sets, songbird sets, birds of prey in miniature, hunting decoys. But never commit to something you cannot deliver, as you will destroy your credibility. In 2000 I came up with the idea of creating something I called “The Millennium Collection.” It consisted of 16 pairs of fancy hunting decoys of unusual species. There were only 50 sets, each signed and numbered. I delivered three or four pairs a year to each buyer. The collection sold out, with gross sales of $240,000. I share this information to demonstrate the power of collections.

-

Buy and sell the work of other carvers. Find a carver who does few if any shows and produces work in specialized areas, such as miniatures. This will be a threeway win: It will give you something to sell, it will help the other carvers, and it will provide added variety to your own customers.

-

Teach classes. This helps in many ways, not least by making you a better carver. It also expands the marketplace because each person coming into a field comes with relatives and acquaintances who can help generate interest and become potential buyers. Each student is worth, at least, a thousand dollars their first year from fees and merchandise.

-

Barter. One of the most profitable methods of selling is through bartering. You can exchange your carvings for dental work, automotive repairs, or almost anything. I have found it interesting to trade with other artists. You can build a valuable collection this way.

-

Write a book. (I have written 14.) Find a need and write a book to fill it. This will give you great credibility in your field and give you something else to sell, as well as royalties when someone else sells your books.

-

Write articles for various publications (like this one). Do shameless self-promotion by appearing in newspapers and magazines and online. If you don’t toot your own horn, who will? Besides, there are always people out there who know nothing about you or your art form.

-

Volunteer. Everyone has a variety of skills. Make a contribution to your field. Many people who never carve or paint provide a venue for us to sell or promote our work and get nothing in return except the knowledge that they are part of something exceptional. In my experience, many exhibitors never even thank the show organizers. They seem to feel that paying the table fee is enough. It is not. Thank the folks who make it possible and help out at their shows. I have been on both sides of the fence, so I know. I have worked on many boards and show committees and have found the experience to be very rewarding. When you participate this way you also become part of the decision-making process in your field.

-

Participate in local auctions, shows, art shows, and things like Ducks Unlimited. (I was an area chairman and regional vice president and sat on the national board of directors as well as the national membership committee.) Get involved with your local D.U. chapter and other conservation organizations. For example, my daughter once attended a D.U. meeting in Texas and left with nearly $2,000 in orders, while also forging potential relationships with other chapters.

-

Always promote the work of others. Never denigrate the work of anyone else.

-

Encourage others to come into the field. When I started 50 years ago, the old-timers would not tell me much. They honestly believed that newcomers provided a threat to their own income. However, in reality newcomers expand the marketplace for everyone.

-

Improve your display. Your display is critical. Lighting is very important. YOU CANNOT HAVE TOO MUCH LIGHT. Utilize your space wisely. Choose a table covering that will complement your carvings and draw attention to your work.

-

Research. I recommend consulting Marie Bongiovanni’s book How to Sell Your Carvings, where you will find tips from many other carvers.

-

Be consistent. Show up regularly at shows with credible work and displays.

-

Work on carvings at shows. This encourages conversation and creates an appreciation for the finished product. People can see the work and the skill it takes to create

-

Keep changing the work on your table. Always have something new (as much for you as for your customers). You must remain fresh. If you are bored, your potential customers will be bored, too.

-

Create perceived value. It is difficult to price your own work. If a piece has not sold for a long time, raise the price. The customer must perceive value. If you do not think a piece is worth much, neither will customers. So, raise the price. Sometimes the problem might be with the mount. Many years ago, a friend of mine owned an upscale restaurant and sold a lot of my work. One piece, though, would not sell. I decided it had to be mounted differently. I took the piece home, remounted it, and it sold within a week.

-

Offer something free. The most powerful word in sales is “free.” Devise some way to use this power, whether it’s a free feather pin or free shipping. This is especially helpful with Internet sales.

We all can agree that shows can be expensive, with table space, hotels, food, travel, and other expenses. It is necessary to cover those expenses and make a modest profit. I hope the preceding will, in some small way, help you do that. Most important: Keep carving!

An osprey is another bird with loads of the “wow” factor. This osprey, which was completed by Peggy Jahn, one of my students, is on permanent collection at the Ward Museum of Wildfowl Art in Salisbury, Maryland.

During his long carving career, Bill Veasey has served as a Ducks Unlimited chapter chairman, Maryland state chairman, regional vice president, national board member, and national membership chair. The Easton Waterfowl Festival named him to its hall of fame in 1994, and in 2015 the Ward Foundation named him one of its Living Legends.

Read NextMaking Feet