A Toucan Decoy

This chestnut-billed toucan smoothie is designed to attract the real birds.

Since the mid-1970s I have been carving decoys, mostly waterfowl, shorebirds, and some herons. I started making seabird decoys years ago, first to complement rigs of sea duck decoys and secondly to attract species to the boat on birding trips. Since trading in my shotgun for a camera, I now make decoys to entice birds in closer for photography.

I started making “photography decoys” about 15 years ago, when my wife and I were planning our first trip to Costa Rica. Thinking it might be fun to use a few decoys in the rainforest, I decided to make toucans. Before long, I had a pair of keel-billed toucans and a single chestnut-mandibled toucan. Seeing them hanging from trees in the rainforest was thrilling. Even more exciting was the reactions from biologists and ornithologists who told me that they had never seen anything like them before.

How did the decoys work? Well, that is another story. At the time, I had no idea how toucans behaved in their natural habitat. I quickly discovered that toucans spend most of their time in the tree-top canopy, much higher than I could place my decoys. But toucans did fly over them and once perched nearby. I had more success on later trips once I learned how to display the decoys properly. Birds often decoyed to them as though the decoys were part of their flocks.

The chestnut-mandibled toucan (Rhamphastos swainsonii) is also known as the Swainson’s or blackbilled toucan. It is common on both the Caribbean and Pacific slopes, and in the higher elevations in Costa Rica. Its close cousin, the keel-billed toucan (Ramphastos sulfuratus), is the only other species of toucan in Central America and Costa Rica, but it is found only on the lower slopes of the Caribbean side. The chestnut-mandibled variety is Central America’s largest toucan, with males reaching 22 inches in length. The females are smaller. The nominate subspecies (and identically marked) Choco toucan from Columbia and Ecuador is larger and heavier.

Toucans are cousins to woodpeckers. They nest in tree cavities, often holes abandoned by the pale-billed and lineated woodpeckers. Toucans feed mostly on fruit, but are also opportunistic omnivores that dine on beetles, insects, lizards, frogs, and small snakes. They do occasionally plunder bird nests for eggs and hatchlings. Their long bills are well suited for reaching into nests and nest holes, something I have seen them do on more than one occasion. The nares (nostrils) of toucans are on the top of the bill on the inner edge of the basal line. They are rear facing, which is an adaptation for breathing while reaching deep into large fruit, bird nests, and nest holes.

The concept for this toucan smoothie sculpture came when my wife, Jen, and I were watching a family group of five chestnut-mandibled toucans feeding on mangoes in Orotina, a small town on the Pacific slopes of Costa Rica. One of the adults was reaching down to grab at a small cluster of mangoes to feed its fledglings. “The posture of that toucan would make a nice carving,” Jen said. I agreed.

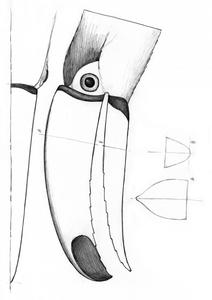

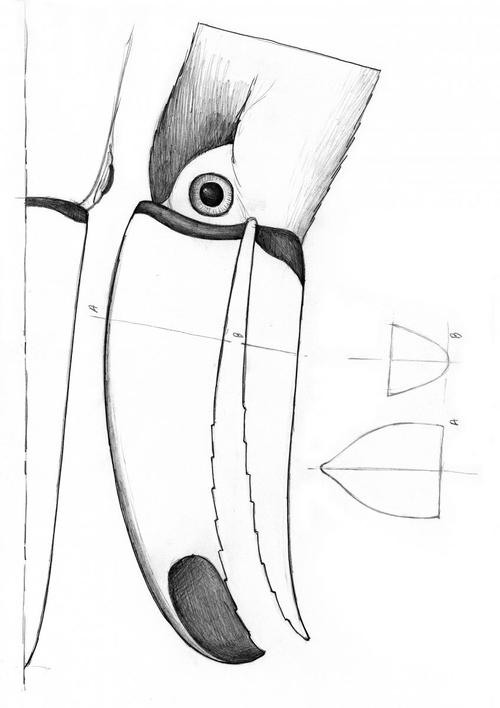

I designed this as a functional decoy, but added extra features and details to complete it as a smoothie sculpture. This carving features a realistic posture with twisted head and body movement, carved feathers, open realistic bill with a tongue, paint-textured surface, realistic painting, and a sculpted base. I carved the body from tupelo, with the bill carved separately. I used holly for the bill because it is strong and has a denseness that allowed for fine detail, especially in the tomial serrations on the bill’s cutting edge. For the very long and narrow tongue, I used greenheart wood (Ocotea rodiei), an incredibly strong wood from Guyana that also holds amazing detail.

Before I even cut out the body and head blanks, I completely carved and finished the bill. Even for a closed-bill carving, I will cut out the maxilla and mandible separately and match them together when I complete them. I do this because it makes it much easier to reproduce the tomial serrations effectively and realistically in the hard holly wood. For an openbill carving, I continue the carving process by reproducing the contours of the inside of the maxilla and mandible. When the bill is completed, I transfer the basal line shape to the pattern to insure a tight match and fit to the body blank.

To rough-shape the bill, head, and body, I use large, cone-shaped Typhoon cutters in both coarse and medium textures. On the bill, I use the medium texture cutter, but on the body, I start with the coarse and then switch over to the medium. Once I’m done rough shaping, I switch over to a large bullet-shaped carbide cutter with a 1/8" shaft. I will refer to this as the “carbide cutter” in the text. I use this cutter for about 90% of my carving after the initial rough-shaping. I use it to smooth the surface by removing the heavy scratching left by the Typhoon cutters, shape the overall carving, delineate feather groups, add details, carve feathers, and more. There are only four other cutters I used on this carving: a small pointed carbide (for the details on the bill); a long, pointed carbide cutter to create the nares; a medium-sized flame carbide to pre-carve and shape the feather edges; and a long, flame diamond carver to finish the edges of carved feathers.

Read the rest of this article in Wildfowl Carving Magazine's Fall 2015 issue.

Read NextEastern Bluebird, Part Two